Dormant

Dormant

13

In Fig’s girlhood, a trader visited the town beyond her home. A rare and expensive treat — those who survived journeys to burgeoning settlements called for high prices to offset their peril. The man had arrived early, before the sun fully rose, and laid a wide mat in town center upon which to arrange his wares. He had rehearsed how to introduce each item as he placed it: candlestick, gravy boat, perfumes, wind chimes, spiraling relics of a long-dried sea. When the townsfolk awoke and news spread, they had piled over themselves like ants. Few could afford his wares but widened eyes had no price. The wealthiest among them — blacksmith, apothecary, wool trader — had claimed fine items with puffed chests. Fig had crawled on her hands and knees with the other children, held her breath against the jostling of the crowd.

At the center of the mat had been one of the most beautiful things she’d ever seen — a doll with flushed cheeks like plumberries and hair finer than sable fur. The trader had followed her gaze and smiled. One hundred percent silk, he’d crooned. Softer than the inside of your ear, face of pure porcelain.

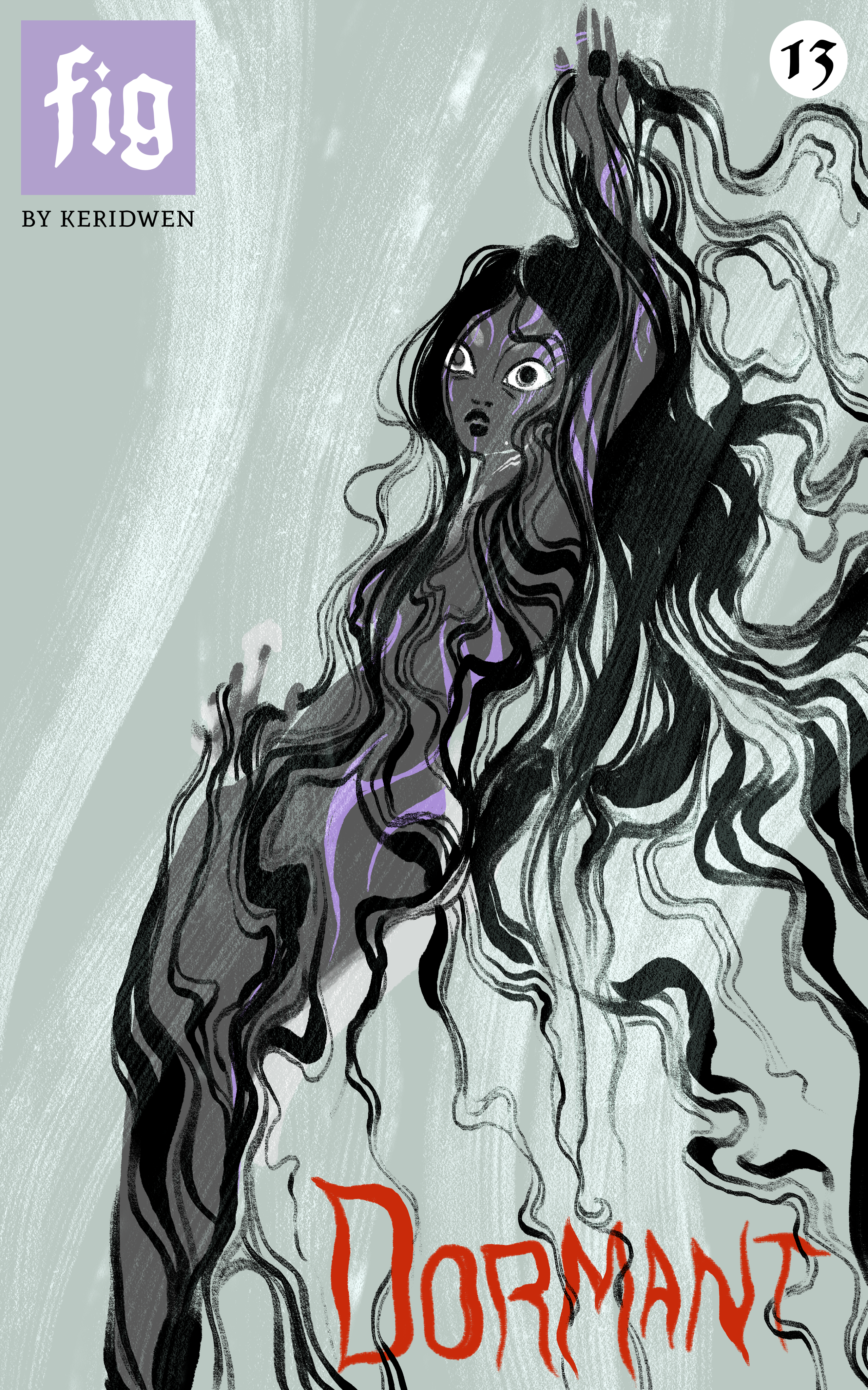

Iraya was the doll come to life. Her body nestled into the thick down bedding as if on display, too precious to make contact with the ground. She had long, dark hair that draped over her forehead and fell to the floor like spilled ink. In sleep, her features were sloping and gentle, her mouth parted just slightly over sharp teeth.

Most strikingly, she was the perfect image of Fig’s mother. She had the same tan skin, pointed chin, hollows beneath her cheeks. Purple ink cut her features from forehead to chin. Fig had seen her mother in her dreams, in the memories she kneaded each night like dough beneath her hands, but to see this doll of her mother, utterly lifeless, staggered her.

Feeling rolled over Fig in waves — weeks of repressed guilt over leaving her home, anger over the demon’s revelations, frustration, fear, hunger, exhaustion, longing, longing, longing. Oh, how she missed her mother. Missed the sound of her footsteps around the house, the smell of her like saplings in rain, the rake of her fingers through Fig’s hair in the dark. She would know what to do if she were here. Instead, Fig was alone with her corpse.

Fig tasted tears in her mouth before she realized she was crying.

“Are you alright?” Akane whispered from behind her. Fig had forgotten the woman was here. Her soft tone only weakened Fig’s will to contain her desperation. In a breath, she was crying harder than she could ever recall. Wood and straw absorbed the echoes of her sobs and encased the room in dull silence.

She didn’t know how much time passed, but took clean towels from Akane as the woman offered them, then dirtied each one with tears and snot. When it was done, she felt like a flower hung upside down to dry then collapse into dust.

“You can take a break,” Akane soothed her, one palm flat on Fig’s back. “We can return in the evening.”

“No,” Fig insisted. Her eyes were so swollen it hurt to blink. She turned back to her sister, each moment an eternity.

In truth, that’s what she was — a sister. Not her mother, their mother. There must be some difference, some distance. She searched Iraya’s face again. With a hitch of her breath, then a sigh, she found it — a mole at the edge of Iraya’s jaw. Their mother did not have that. In fact, Iraya’s eyebrows were less angular. There was smoothness where their mother was lined, a release of tension in her mouth. Her sister had an openness Fig had never seen in their mother, even when she, too, was lost to sleep.

Emboldened, Fig leaned closer. There was a chunk missing from the bottom of Iraya’s far ear trailing a puckered scar across her neck. Her tattoos had parted and healed misaligned.

“What happened to her?” Fig asked, mouth agape.

“I don’t know,” Akane admitted. “That was healed far before she arrived.”

“How long has she been here?”

The older woman folded her hands into her sleeves. “A decade, in the spring.”

“What?” Fig swallowed. “She’s been asleep that long?”

“She stirs, at times,” Akane said. “Sometimes when I bathe her I see her mouth moving, as if she’s speaking.”

Fig lowered her voice to a whisper. “How do I wake her?”

Akane’s face dropped, but she composed herself. “It has been my hope you would know. The seer did not say?”

Fig rifled through the jumbled chaos of her last conversation with Clover. “She did. Something about pulling.”

“I won’t pretend to know what that means.” Akane smiled politely. “I am a caretaker, not a witch.”

Fig felt mounting pressure. Both Clover and the demon implied this was a task she was capable of — that only she was capable of. Akane sat on her ankles but shifted her weight from side to side, impatient.

“Can I touch her?” Fig asked, unsure.

“Please.” The older woman nodded.

Fig sat on the edge of the dais and felt for magic. There was nothing — less than nothing, emptiness. The space above her sister was cold with the absence of magic. Holding her arm above Iraya’s chest felt like hovering in the snowfall beyond the gate. Perhaps she, too, had lost that part of her?

With slow hands Fig pulled back the blanket covering Iraya’s torso, exposing just her right arm. She wore a red cotton robe with neat stitching. Protruding from the sleeve, a roughly calloused hand littered with healed scars. Long, jagged lines paler than the rest of her skin ran over her wrist, knuckles, palm. Fig gasped. The scars shattered the lines of Iraya’s tattoos like cracked crystal. Fig remembered smearing blackberry juice over her body to mimic her mother’s tattoos as a child, how the dried pigment would rub and split as she ran. She ran her thumb over one of the scars. Iraya’s skin was cold to the touch.

The air of the room simmered with anticipation that quickly dissipated. Iraya’s chest still rose and fell in shallow breaths. Fig heard Akane sigh.

Fig turned to address her. “You thought just me touching her might wake her up?”

“I’ve seen stranger,” the woman insisted, her brows furrowed. “Do you feel anything?”

“No.” Fig shuddered. “If it’s some magic keeping her asleep, it’s deeper than I can access.” She remembered Clover’s hurried explanation, I’ve worked quite hard to push her to the surface. It didn’t feel that way. Fig had never seen a sleeping person so empty of spirit, had never felt anything as empty of magic except herself.

Fig and Akane sat together as the sun set, its warm light diffused by the paper walls. Fig strained herself digging for any sort of magic on the dais but failed and failed.

“You should rest,” Akane finally interjected. If she was disappointed she did her best to hide it. “Shall I escort you to the visitor’s quarters?”

“No,” Fig declined in a panic. She had journeyed so far to make it to this room. The idea of leaving before the work was done terrified her, as if Iraya might wake and escape in the night.

“I understand.” Akane bowed her head. She moved back to the closet to fetch rolled up bedding similar to the one swaddling Iraya, plush and white. It unfurled like a cloud. “One moment,” she said before exiting the room to ring an instrument beside the door not unlike the one Cathea had used to summon the dove.

A second woman, younger, appeared in the same white robe as Akane. She peeked through the door at Fig with curiosity.

“Please bring guest robes and dinner,” Akane requested, stepping to the side to block the entryway.

The woman blushed, chastised, then scurried away.

Akane closed the door. “Excuse her, your arrival is of some interest.”

“Is it rare to get visitors?”

“Yes,” Akane answered. “Few find solace in seeing those they care about so transformed. And for many, any who would visit them are long dead.” Fig shivered. Akane warmed her voice. “Though it is also because my fellow attendants know of your sister’s situation. It is an exciting prospect to think one of our charges may recover.”

“What makes you think so?” Fig asked, doubt pulling her arms across her chest.

“The seer said her kin would come for her. That kind of assurance is rare,” Akane declared. “Though, in a way, I expect all of our wards to recover — even if it is long after my time here ends. Dove wrote that hope is a kind of magic. It is what makes our work important.”

The second attendant returned before Fig could ask further questions. The smell of seared fish sent her stomach grumbling. The woman brought a low table and tray of dishes: an entire fish, rice, pickled vegetables, eggs, dark sauces, dressed leaves that Fig did not recognize. Compared to Cathea’s thin soup and the meager meals Fig had eaten on the mountain, it was a veritable feast. She descended on the tray as the attendant placed two gray robes beside it and disappeared as quickly as she’d come.

“These will let the rest of the Asylum know you’re a visitor, not a ward,” Akane explained, gesturing to the robes. “Wear one if you leave this room.”

Fig nodded around mouthfuls of fish. The meat was hot and tender, generously salted. She had to rip herself away from it to watch Akane carry a second tray to Iraya’s side and spoon food into her mouth.

“You do that every day?”

“Multiple times a day.” Akane smiled her small smile.

Ten years was half of Fig’s life. Akane had been here, keeping Iraya alive, since Fig was a child. The expanse of that time horrified her. She returned to her meal with less enthusiasm.

Her work complete, Akane gestured at the bucket and faucet by the door. “You may use the towels here to wipe her head with cool water. She experiences occasional flashes of heat, though I have not discerned a pattern.”

Fig blinked against exhaustion. “My hope is that Clover will visit me tonight with further guidance.”

“We share that hope.” Akane bowed her head and left.

Fig ignored how strange it felt to be alone in the room with her sister unconscious. While it was a place of healing with Akane present, cold descended in her absence. Fig stripped her soiled clothing and wrapped herself in one of the robes before sliding into bed as far from the dais as she could.

Sleep was not defeat, it was the path forward. She was so close to her goal now, which meant Clover was as well. Fig reassured herself, as she closed her eyes to sleep, that the seer would return.

She did not. Fig woke to blue, paneled shadows cast over her like a net. She had slept deeply, dreamlessly. She closed her eyes again, willing Clover to burst forth.

She was late, perhaps. Waylaid.

Nothing.

Fig stomped to Iraya’s bedside in frustration, half-expecting the noise to wake her. The seer had troubled herself thus far just to abandon the plan at its end? Clover had described Iraya as a point of strengthened power, a conduit. Fig felt no such magic, no life behind her sister’s closed eyes. When she rested the back of her hand on Iraya’s forehead it was cold like stones in the river. She lifted her sister’s arm by the wrist and let it drop to the bed with a muted thud. She grasped her by the shoulders and shook. She said her name, softly at first, then louder, louder.

“No dreams, then?” Akane interrupted from behind her. She carried two more trays of food.

“No.” Fig sat back, embarrassed.

Akane sighed. She gestured for Fig to join her at the table and watched as she devoured a new selection of pickled vegetables and rice.

“Pardon my ignorance,” Akane began, “but is there precedence for such a thing among your pack? The kind of sleep she’s in?”

“Not that I’m aware of,” Fig answered carefully. She did not understand the rules of this place. If Akane assumed she was a witch, she would not correct her. And if she was truly alone in her task, she needed more information. “Did Iraya have anything on her person when you found her? That might aid me.”

“Yes.” Akane nodded. “One moment.”

When the woman opened the door to step outside, Fig saw a procession walking down the path. Attendants in white robes like Akane’s guided four people in red, like Iraya. Those in the red robes walked slowly, strangely. Two held on to their attendant’s arms, their eyes wrapped in red fabric. Before she could look more closely, Akane shut the door behind her.

Fig felt for magic through the screen. What she found was muffled, scrambled — as if someone tried to speak to her with her head underwater. She drew back.

“Here.” Akane returned with a traveling pack, folded clothing, and a roll of leather. She deposited all three in front of Fig before stepping out for more. “And this.” She labored with a weapon a head taller than her with a long shaft like a spear but tipped with both a wicked metal point and the blade of an axe.

Fig stood to help her bring it into the room and buckled in surprise at its weight.

“What even is this?” she exclaimed.

“How should I know?” the woman huffed, exhaling loudly as she brought the beast of a weapon to the floor. “Haven’t laid eyes on it in a decade.”

Fig ran her hand over its long, wooden shaft. The wood was smooth and shiny in two places. She rested her hands there and felt the indents of hard use. If the weapon had any magic, she couldn’t hear it.

She moved on to the roll of leather.

“The wrap is ours, it’s what Jigo recommended for storage,” Akane noted.

Fig unrolled it to reveal a line of knives of varying sizes. Thin and small for tucking into boots and sleeves, larger to be holstered at the thigh, the largest to be kept on the belt. Though the materials used for the handles were unfamiliar, she recognized the size and shape of each. At the very end, the smallest, a curve that was most familiar. She picked it up gingerly. Its weight and balance were unmistakable — one of her mother’s throwing knives.

“Anything helpful?” Akane prompted.

“Not yet,” Fig whispered, choking on sentiment. She needed to focus.

She reached for the pack next. When she undid the two clasps holding it shut, the foul, rancid stink of demon magic washed over her.

“Ugh,” Fig covered her mouth and nose with her arm out of reflex. It did not help. The foulness was in her mind, tendrils crawling around her skull.

“What is it?” Akane asked, perplexed. It seemed she was completely unattuned to magic.

Fig reached for the source of the magic, familiarity fighting against her unease. She knew this scent. Not just demonic, not just foul — specific. Acidic. She pulled her hand from the bag to reveal three dried hare’s feet. Each was tied at the joint with twine and secured to a loop of leather like a desiccated ring of keys. If she had not recognized the exact match to the foot she’d found in her garden, the scent and taste were unmistakable. Severed feet of the demon Lepocapra.

“Are there magical defenses to the Asylum?” Fig swallowed and tried to calm her voice. “Besides Jigo and the monkeys?”

“Yes.” Akane tilted her head. “The steam from the baths cloaks all manner of magics. They say no one has come in or out without permission since our founding.” She hesitated. “At least, alive.”

“Good,” Fig declared and put the feet back into the bag. It would serve no one to summon the demon here. The memory of its slick fur and blinking eyes made her cold all over.

She already knew her sister was affiliated with the demons, she reassured herself. To find such a thing should not be a surprise. But Fig could not contain the sheer enormity of her unease. Why would Iraya be in possession of not one, but three tokens of the hare demon? Did each represent a separate deal? What of herself had she sacrificed, and then had more to give?

Most staggeringly, did their mother know? Had Iraya dealt with demons before or after their separation? Even if Fig could bring the hare here to ask, it would be of no help — both Lepocapra and Cervus had refused to speak of the details of her sister’s fate.

Fig dug through the rest of Iraya’s belongings with no further revelations. Though there were some trinkets of interest among the survival equipment, none contained magic Fig could sense. Her sister’s leather clothes were tattered beyond recognizable style and soaked through with dried blood. Fig braced herself for some commotion upon touching the blood, but found none. If there had been magic once, it was long gone.

“Anything?” Akane asked.

“No,” Fig admitted. She pushed the bag back toward the woman. “But keep that dry at all cost.”

Akane only nodded and placed both bag and clothes into the back of the linen closet. The strange weapon she propped up in the corner or the room. Perhaps her hope had not dwindled so much she had given up on Iraya waking soon, wanting her possessions nearby.

“She’s not physically broken,” Akane turned to say after a moment, determined. “Forgive my intrusion, but I’ve had quite a while to think about it.”

“Please, intrude,” Fig insisted. She took deep breaths to steady herself, the hare’s tokens’ rancid magic masked some by distance.

“She’s receded within herself,” Akane explained. “The seer must have meant she intended for you to pull her out. Have you done magic like that before? Of the mind?”

The aching emptiness in Fig’s chest was becoming too familiar a companion. It roiled in desperation at the thought of her doing magic.

“I speak to Clover in my sleep,” Fig began, swallowing against the feeling. “For the trials, she insisted on merging our minds, but she initiated it. And there’s nothing I do to summon her, or call to her.” If that were so, the seer would have come last night, or in the moons Fig had traveled with the caravan.

The caravan. Fig catalogued all the strangenesses they had encountered in the wilds, all the different flavors of magic she’d encountered and clung to. Iraya was an occultist. Had Helmina, Ao, and Ferris used magic of the mind? Not that Fig had noticed. She reached for the vial of the Nimble’s blood at her hip as she did often to remind herself that their meeting was real, not a manifestation of her loneliness, desire, shame. Her hand met only fabric — she’d forgotten she’d changed.

But — that was it. She sat up straighter. She had done magic of the mind. She remembered the moment she’d touched the Nimble’s blood as she’d jumped for the vial in the storehouse, how just a drop had drawn her into its head, had fractured her along the path of its snout cutting through time. Her limbs had felt so loose when she’d returned to her body — too short, too slow. Fig thought of Cathea’s disdain in the morning, echoed through a sneer: If your stink wasn’t enough, that look on your bloody face in the sunrise would do it.

“Do you have a sewing needle?” Fig asked Akane, urgent.

“Yes,” Akane confirmed, alarmed by the sudden air of excitement. She returned to the storage shelves to rustle through wooden boxes of supplies.

Fig jumped up to pace the room, the woven fiber of the floor bouncing beneath her feet. “And a bandage,” she added. “Just a small one.”

Akane obliged, opening a different box. Fig took the materials from her and bounded to the dais.

“I have accessed a Beast’s mind through its blood,” she explained. She unearthed Iraya’s arm from its bedding and turned her scarred palm. Akane watched from behind Fig’s shoulder as she pricked the top of her sister’s pointer finger. Iraya’s flesh parted like the mouth of an oyster, yielded a pearl of luminous blood.

Fig took a shaky breath. The blood consumed her focus, warped the room to a sphere pulsing around the single drop. She could no longer sense the presence of the woman beside her, the rough woven floor beneath her feet. Only warmth, wind through chimes, ash on the surface of her skin.

She pressed her finger to the blood.

She was drowning. No — not drowning, drinking. A thick, dark liquid spilled over her chin and neck, down her chest to the ground. It was warm against her skin but fire against her throat. Molten. She was burning from the inside out. She could hear her pack chanting. The words were incomprehensible. Only sounds. Only beats. Only music in a rhythmic eternity of heat and pain and beginning.

She felt their eyes on her, then herself from their eyes. With each blink she found herself at the edge of the circle, looking in. Each moment a different angle — the front of her daysbane dress, the slick of her hair, the blood dripping down her arms and falling to the grass. The pack began to dance. They clasped hands. Moving from face to face did not stop the burning. Her head began to swirl as they undulated, their features blurring together.

But there was one face missing. One face warped as if a thumb had reached into the universe and swiped its contours flat. The harder she looked for it, the more it shifted away.

The burn was down in her stomach, now. Her throat flamed as if its flesh would melt and leave only a metal sculpture of her innards. She opened her mouth to scream.

Fig opened her eyes to meet Akane’s. The older woman was upside down. No, Fig was on the floor. There was some terrible noise. She swallowed, and it stopped. She had been shrieking.

“What happened?” Akane asked, her face pale. She brought a wet towel to Fig’s forehead.

Fig clawed at her throat. When she spoke, it was hoarse. “A memory, I think. It kept moving around.”

“Moving around?” Akane pressed.

“There were so many people. I was all of them — I could see through all of them.” Fig’s head spun. She squeezed her knees together to ground herself.

“Incredible,” Akane breathed. “This is good.”

“It doesn’t feel good,” Fig moaned. When she’d merged with Clover’s memories there had been a cloudiness at the edges, an emptiness, the weightlessness of dreams. Iraya’s mind was sharp with immediacy, pain.

Fig gestured for water and gulped it in earnest. Her shaking hands spilled the liquid over her chin, blessedly cold. With enough breath, she convinced herself she was not burning, not drowning. She was herself.

The woman cleansed Iraya’s finger and wrapped it in white linen.

“I want to try again,” Fig resolved. She shook out her limbs and rolled her neck.

Akane prepared a second needle.

Her leg was bleeding. More than that — a chunk of it was missing. She limped forward as blood ran down her thigh, exposed sinew pulsing. Her prey crawled away from her using only his arms. He was barely moving, his own ruined legs dragging behind him in the grass. She stalked him loudly. Messily. No one around anymore to hear. His heart raced loud enough to reach her.

Please, he moaned. I have more to give.

No use. They always begged in this part. So many chose to end things begging. She would not greet death that way, she decided. Desperate and pleading. She pressed her boot against his chest and felt the suede grow heavy with blood.

A chorus of whispers filled her ears. Today it was gibberish. She was more tired than she’d thought. She felt her mouth form words but could not hear them over the voices, their empty syllables like a rush of water. No matter. Her words were always the same. Her prey’s pleas for mercy did not vary much.

She took a deep breath. With the exhale, she swung her halberd into his neck.

Fig returned to herself shivering. She had rolled onto her side and clutched her thigh. She felt seared by the pain of torn flesh though she could feel her skin unbroken, cold as if she had plunged into the ocean at dawn. But it was dark everywhere — night had fallen over the Asylum.

Akane returned to her side from across the room. “What did you see?”

Fig shook her head and bit the inside of her cheek. All she could picture was the face of the dying man — his body bloodied and ruined, his arms straining away from her plodding, methodical steps. The stench of fear rolled off him and filled everything. She saw the creases on his face as he pleaded for his life. She could feel so clearly how easy it was to kill him. How the weapon parted him like freshly turned soil. How life left his eyes, how little she cared.

She cried. Big, fat tears warmed her skin.

Akane touched her arm. “Let’s take a break.”

There was a dedicated hot spring for visitors. They weren’t meant to cross paths with any ward they were not here to see, Akane explained. When Fig had first dipped a toe into the steaming pool, it was hotter than any bath she’d taken. She’d yelped and drawn back. Akane had only laughed and beckoned her forward. After a few minutes to acclimate, fearfully at first, and then with a sigh, Fig submerged to the jaw in the steaming, fragrant water.

“Nice, isn’t it?” Akane covered her mouth with her hand to hide a smile.

Being in the water was like floating, like all of Fig’s joints were relieved of their duties and filled with air. “Very,” she exhaled.

A group of monkeys had waited for them to enter the spring, then came with candles to light the lanterns that lined the edge of the pool. When Fig tilted her head back, she could see the stars larger than ever. This was the highest she’d been, the closest to reaching up and plucking one from the sky.

“Akane, do you have a sister?” she asked, her face cool in the mountain air.

“I have six.”

That retrieved Fig’s attention. “Six?” she exclaimed.

“My mother was quite pleased with herself,” Akane continued. “To have seven of us felt quite auspicious.”

“Are you close with them all?”

“Not equally,” Akane mused. “Some of us do not get along. Others feel a kinship unlike any other. That is common, to my understanding.”

“She isn’t who I thought she’d be,” Fig whispered. Her mother was violent, but the core of her was anxious — defensive. She was fierce in the name of protection, self-preservation. Iraya’s mind boiled with a rage Fig had never experienced. A pain that lashed forward like a whip, like the edge of that halberd through the man’s neck. Fig felt in the texture of the memory that this man was not the first her sister had killed, nor the last. Fig shuddered against the routine of it — worse, the boredom.

“You’ve only just met.” Akane closed her eyes. “Two memories do not make a witch.”

“What if it were bad for her to be awake?” Fig asked, her voice shaking. “For her, or for those around her?”

“She deserves to be awake,” Akane insisted, her voice suddenly firm. “Dove’s doctrine is that we turn away no ward, do not judge whom we help. If your sister has wrought woe, may it catch up to her outside these walls. It is her right to live to see it.”

“I see.”

“You may wake her, leave with her, and then decide she must die,” Akane shrugged, relaxed again. “We do not oversee such things.”

“Would you do that to your sister?” Fig asked incredulously.

“If the wrong one caught me in the wrong mood,” Akane muttered. When she slid further into the water, Fig could not tell whether the ensuing bubbles were wrought from the spring or her laughter.

The Asylum kept tubs of water with which to wash before and after visiting the springs. For the first time since leaving the caravan, Fig took the evening to rinse and detangle her hair. She carded through it with inexperienced hands — it had been her mother’s favorite chore. She had been endlessly fascinated by the waves in Fig’s hair, so unlike her own, straight like wheat. So unlike Iraya’s. The uncanny similarity between the two was no small object of Fig’s fixations. She resembled her mother, sure, but Iraya was near identical — as if she were pottery poured from the same mold.

Fig stilled her hands. There were two kinds of witches. Born, like herself, like Vaani — and created. Created from nature, like Ao or Ferris, or created by another, like Helmina and her bludsora, whatever exactly that meant. It was possible their mother had created Iraya. More, if so, she had created her in her own image.

Fig felt an unease grow deep within her, deeper than the calming magic of this place could penetrate. She tied her hair into braids and returned to her sister’s room.

Akane had left her needles, the cleansing water, and bandages. Fig was not to prick the same place twice or use the same needle twice. If any stage of the process hurt Iraya, she did not show it. And so Fig reached for her third finger and squeezed out the small pearl of blood. It whispered to her in a faint, smooth voice. The last two memories had been vivid, but short. She felt no closer to the inner part of Iraya that lay sleeping — she needed more. Fig squeezed the wound further until the pearl grew larger, larger, then spilled over Iraya’s finger into her palm.

This time, Fig resolved to focus on the faces she remembered from the first memory, to distance herself as much as possible from the second. Perhaps with enough will she could guide the flow of what she saw. Fig thought only of the chanting voices as she flattened the bead of blood between her hands.

Iraya, we have a surprise for you! She laughed a laugh that was not her own — deeper, rounder. There were no surprises anymore, not really. She had felt their rumbling excitement for the last press of the moon from crescent to half. They’d practically vibrated in their sleep, interwoven with her like roots. Her pack had been planning something.

Her pack. The words burned with pride in her chest. Each of them had been careful to keep it from her, in their own way. Isodel thought continuously of weaving. Jorem recited old firesongs on repeat. But she could not miss the parts of it that were important — the preparation, the focus, the joy.

Three of her kin picked her up, their locked arms a makeshift throne. She laughed again. They lifted their arms to throw her, and another set caught her. They laughed and laughed and laughed. Pleasure in the pack was multiplied in each of them, a spiraling loop of giggling like shouting in a cave. She felt around for the only mind missing. Gone again. Too far to be felt. The others sensed her disappointment and folded her in closer. Almost there, Iraya. Just a little more.

Iraya, Iraya, Iraya. Their voices repeated, echoed, grew distant. When her feet touched the ground, she was somewhere else. She collapsed beside a meager fire, coughing in the cold. It had been years since she’d slept with them, tangled together like bonfire planks.

Tonight, she was alone. Magic pulsed against her bones. Some nights she felt it might boil her, that she would wake with cooked flesh to be picked apart by birds. Iraya, we’re sorry. Iraya, we’re angry. Iraya, we love you. Iraya, Iraya, Iraya. Alive, their thoughts had been weightless. Her own mind multiplied, freed from solitude. Dead, each hung from her soul like a jar overflowing with sand. Iraya, we miss ourselves. Iraya, we’re lost. Iraya, hunt and kill and rip and burn and run and run and run.

She was running. Her prey tonight had managed to grab hold of her spear. He stopped, panting, to snap the wood across his thigh, brittle like bone. She screamed. She felt all of them scream. The noise bubbled up from inside her, boiling magic expelled.

In a moment, she was on top of him. She was stronger than she looked. Big men like him never estimated her correctly, never weighed the density of her grief. She clawed into his face with her hands. She felt flesh rip and part beneath her nails. Blood spewed from her tears and she felt the force of her magic — their magic — collect it, harden it, wrap around her fingers in pulsing red blades. No, he cried, as if objection would save him. Mercy. Further words garbled as she shredded his jaw.

Fig returned to herself and promptly vomited into the water bucket. Bile stung her throat as she coughed and retched. She could feel the give of the man’s flesh beneath her nails, feel the scrape of his skull beneath his skin. She vomited again.

Iraya lay on the dais, unmoving. If these excursions into her mind disturbed her as much as they did Fig, it did not show. Fig beheld her stillness with new horror — raging beneath the facade of rest was inescapable, roiling violence. Even a trail of thought that began sweetly led to pain, gore, death.

Fig tried to push the final scene from her mind. Though the faces slipped from her, she could remember the joy of Iraya’s pack. Their emotions — no, their entireties — were bonded in some way. She had felt not just their excitement at the surprise but the way their fingers shook, the ground beneath their feet as they jumped. It should hurt her head, to feel such multiplied selves, but the memory was expansive, easy. A more lived evolution of the sensation from the first memory when Iraya’s mind began to flit between the rest.

In contrast, the night at the fire was heavy with the whisperings of ghosts. Iraya’s grief overpowered any other sensation. She was haunted, somehow. Had that pushed her to her current ailment? Pushed her to hunt people like animals?

There was a glancing anxiety, both in the first memory and third. Something, someone missing. Fig had felt the memories warping around this absence and her own mind whirled around it in turn. Perhaps that was the core of things. The center from which she must pull her sister out.

Fig fetched clean water then followed Akane’s instructions for dressing the wound on Iraya’s third finger. Her guess about a larger quantity of blood giving her more access had been right — the last series of memories had been longer, spanned a wider gap in time. She could feel the contentment of Iraya’s mind in its youth and then the fractured fury of years passed. Fig resolved to focus on the blurred figure, whoever Iraya searched for just out of reach.

She hesitated, but retrieved her own knife from her things. She sensed a distance between what she had seen and what she needed to see. A few drops would not suffice. When she returned to Iraya’s side, she found a long, straight scar across her opposite palm, likely cut by a knife of similar size. The blood beneath it sang in a murmur, beckoned Fig forward. She was not creating a new wound, she rationalized, but opening one that already existed. That was better, surely. When it healed, her sister’s ledger of scars would remain unchanged.

She parted the skin slowly, then in a nervous swipe. When she pressed their palms together and interlaced their fingers, warm magic burst from the cold of Iraya’s skin.

The forest was quiet. Everything was quiet. To her roots beneath the soil, the footsteps of creatures were soft as rain. At the tips of her branches, wind blew like the breath before a kiss. There was everything as much as there was nothing. There was sap, there were rings growing in slow, prodding instants. There was time. Ceaseless, solid time. The seasons changed with the laziness of turning over in sleep. The years passed with the rapt attention of the woodpecker, the fury of the storm. A part of her was a witch. But not yet. No, not yet.

Later she sat in the meadow where her trunk lay severed, her body new and stiff. Blackbells scattered around her like ash. They felt different from here. She did not feel them dying as the moon moved. She felt they would live forever. Something was speaking. She couldn’t hear what. The sound was muffled. The sun was warm on her legs. She was fresh. Her arms were less splintered than branches. Her toes curled and uncurled in the grass. There was a blur beside her. The blur was the one speaking, its face like a raindrop, shimmering and opaque. The whole world swirled around that point. She was meant to be here. Even if she couldn’t see, or hear. This was the beginning of where she belonged.

The blackbells were wilted by summer, but she was still there. Her skin prickled with hair that was sensitive to wind, with blood that was sensitive to magic. She moved one leg, then the other, still in wonder of the sinews beneath. So strange. So intoxicating. The blur spoke again. The sun had set in front of them. It spoke softly, though the others couldn’t hear them from here. This softness was just for the two of them. This world was just for the two of them. She tested the joints of each finger like a worm inching over her leaves.

It was night. The blur pulled her onto her back. That’s the water pourer, it crooned, speeding up with excitement. And the hunter. See the brightest star at the end of her bow? It leads you towards your prey. She and her pack guide us where we must go. Pack. She turned to look at the blur. She could hear her now, a voice so familiar it came from deep within her. She blinked a few times. The blur melted, drips coming into focus.

Dark hair, sharp face, lines of purple ink.

Of course. Her mother.

Fig felt herself yanked forward. The force of it was violent, sharp. She was not fully Iraya, not fully herself. It was her in the field with her mother — a different field, but the same sky, same stories. The same glint in her eye, the same emphasis on the tail of each word. The same longing, elongated pauses between phrases, as if the stories were a string to be pulled taut, as if their true treasure might spill from the seams. The water pourer, she said again, her voice slightly deeper, her face slightly more lined. And the hunter.

Her vision snapped. She was back with the blackbells, their stems folded and dead. She was stronger than them. Her entire body buzzed with newness. She used to be a tree. That’s right, she was a tree, and then a witch. Magic flowed to the tips of her fingers.

No. No, no, no. She had no magic. She was empty. The air hummed with nothing but insects and bird calls. She was a girl. She was a child of flesh and blood borne and ripped from more of herself.

She was an abomination borne from betrayal. She was nothing like what had come before. She was a mockery of the dead. She shouldn’t be alive.

Fig released her sister’s hand with a rush of something explosively hot. Fire caught between them and seared the flesh from her palm.

Iraya sat up sharply, every tendon in her neck pulsing. Her eyes shot open to meet Fig’s, her beautiful face twisted with fury.

“GET OUT OF MY HEAD!”