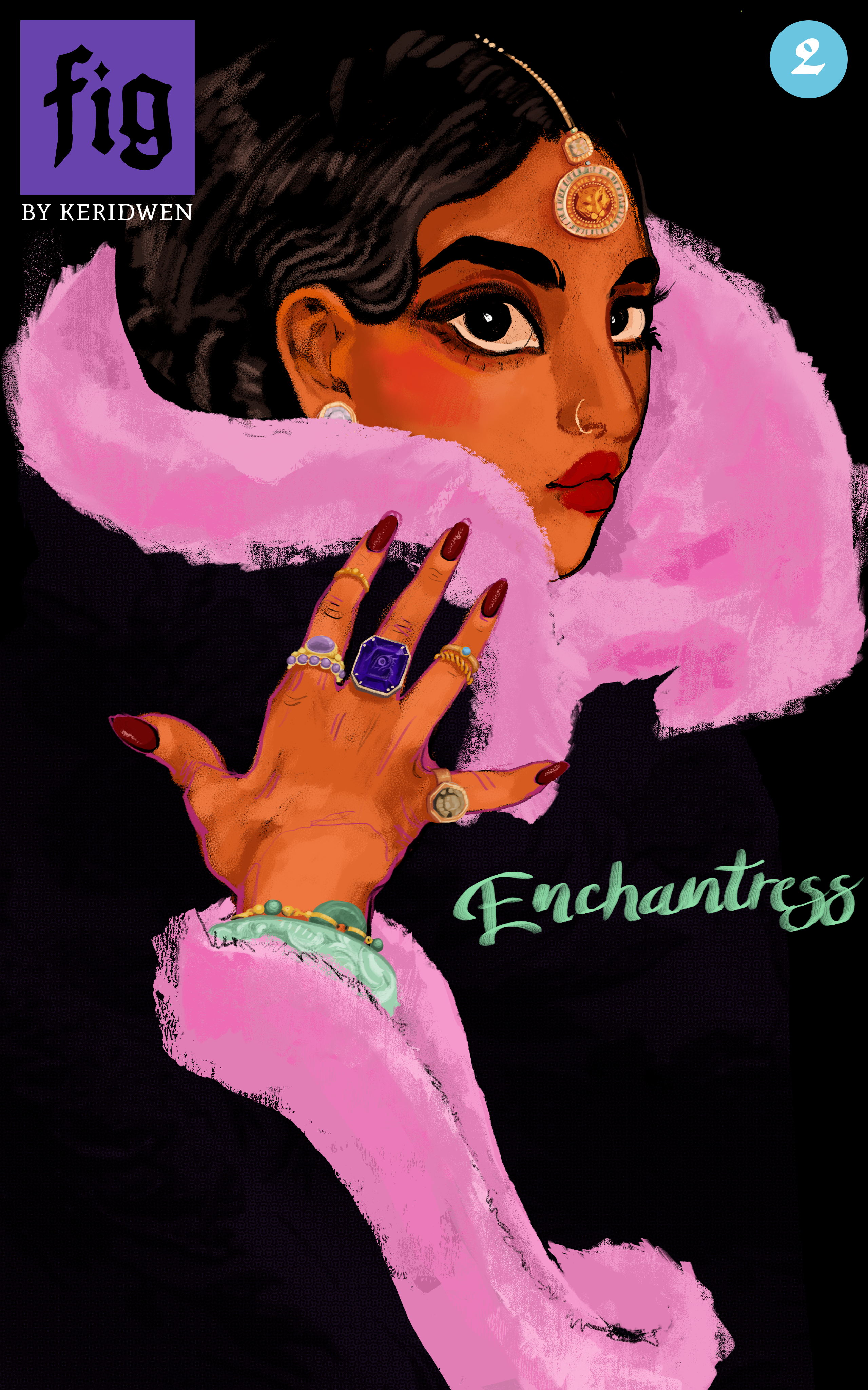

Enchantress

Enchantress

02

The girl's mother had built their cottage while pregnant. It was the kind of origin story she embraced --- a life formed from labor and effort, scaffolded around just the two of them. She, ripping at wood, her daughter, kicking at flesh. She reminisced often on how foreign it felt to have another being living inside of her, completely opaque. What were you thinking then, my sugarsnap? What had you already absorbed, synthesized, into a mind all your own? For this, the girl had no answer. Many days, she wished she did. I thought often of you, mother. Of your strength, your beauty, the evenness of your gait. I learned every song you sang, every story you recited. I traced the shapes your hands made across the tan membrane of the sky. She said none of this. Her mother was no less satisfied. She had a reverence for a closed interior that the girl had inherited against her will.

The cottage itself was sloping and compact. Each room had a purpose: deer-skinned bedroom, jar-filled pantry, fireplace flickering in the kitchen. They spent much of their time outside: gardening, preserving, dancing, play-fighting. When it rained they curled together by the fire and the girl's mother made animals from the shadows of her hands: Boar, Wolf, Bear, Beast. When it snowed they built castles from blocks of ice and treats from syrup and snow. The world was made entire by the ring of trees around their clearing. The girl knew each rock and blade of grass like her mother knew each hair atop her head.

Fig returned from the market to find her mother pacing the yard. She had braided her hair back into three long ropes that writhed over her marked shoulders like snakes.

"My marigold," she exhaled, pulling the girl between her arms. "You were gone a long while."

"The baker had a batch of sweet rolls in the oven when I arrived. I waited for them." It wasn't a lie, but a dodging of the truth. Fig had lurked to the side of the bakery worrying over what to tell her mother and how. It shocked her that the gnawing force of her obfuscation had widened a hole large enough for Vaani to fit inside. She felt the weight of promise in her left palm as surely as her mother's embrace. If the witch meant her no harm, there was no rush to expose the day's wonders to her mother's watchful eye.

"Patient girl," her mother crooned, holding her still. "I need your patience now."

Fig pulled away and caught her mother's face distorted with fear. "What's wrong?"

Her expression smoothed. The violet lines of her tattoos split her features like fissures. "I'm leaving."

"When?" Fig searched every facet of her and found nothing.

"Now."

It was not unusual for Fig's mother to depart on short journeys or hunting trips. She often patrolled the land beyond their home. It was unusual for her to look so shaken, if even for a moment. To leave with so little notice.

"Something of interest to me has appeared at the edge of the wood. I'll be gone eight nights, maybe nine," she said.

"What is it?" Fig whispered. Her blood cooled.

"Likely nothing. A fool's errand."

Her mother hoisted a large travel pack, hardly used. They had never been so long apart. This information hung between them.

"I'll come with you." Fig scanned the yard for a second bag, half-expecting to find one already full.

"No," her mother insisted.

"Why?"

"You'll be safe here."

"And you won't be safe there? More reason for me to come."

Her mother's gaze hardened further. "There is nothing in these woods that could hurt me." She spoke it like a prayer.

"I know that."

"Do not go to town while I'm gone."

"Of course."

Her mother bent to press her lips to Fig's forehead. "We can go to the sea when I return. Hunt for shells."

A treat, then, upon her return. An apology wrapped up in a promise. Her mother rose to her full height. She stood with the sturdiness of the trees. Fig watched her mother's back as she faded into the wood, strained her ears to each silent step. Darkness overtook her like a fly trap winding shut. When it was done, the girl stood alone before their cottage. Her chest hurt. She felt a shiver up the back of her neck --- was this luck? Or a portent? She had no plan for evading her mother to meet Vaani in the evening. She had worried over it like a dog with a stick on her return journey and had resolved to miss the witch altogether, to try and catch her the next day in town to explain. Now, due to some disturbance on the wind, she was free. Free to wander, free to disobey. The thought of it displeased her, but her curiosity overcame yet again. She distanced herself from her worry by unpacking her haul from town.

The giant black alder was a quarter day's walk from town. Greedy for sun, it flourished in all directions and left a grassy clearing in its wake. Fig and her mother visited on occasion for the wild blackberries, thick and sweet, that bloomed at its edges. Fig's mother was not here now. Her absence loomed like an ache. The potential of her fury loomed even more. Fig reassured herself that she would never know of this meeting. By the time she returned, Vaani would be gone. Fig would have only knowledge, secret and private, to show for it. She would chew and swallow the witch's teachings like sneaking stray berries. Nothing would change.

As Fig walked, the alder came into focus. Seated beneath it, her skin glistening in the last of the summer sunset, was Vaani. Today her silk wrapping was a lighter shade of orange, pale like scoops of cream. It fell from her hips and pooled luxuriously in the grass. Gems floated on the oiled surface of her hair and glittered as she turned to spot the approaching girl.

"Punctual. I like that."

Fig had never seen someone so cloaked in excess. She tugged on her linen shirt with a new shyness.

"Come here." Vaani sensed her reluctance and beckoned, bangles tinkling. She patted the grass beside her. It exhaled dreamily at her touch. There was something more deeply entrancing about the witch here, blooming from nature like an orchid.

Fig folded her legs and sat. She opened her mouth to speak, but Vaani kept her hand raised.

"Be quiet. What do you hear?"

Stillness Fig understood. She exhaled and closed her eyes for good measure. It was easier to focus without meeting Vaani's darkly lined gaze. "I hear," she paused, allowed the world to wash over her scalp like the river, "crickets. The wind through the alder. Some animals rustling at the edge of the wood. Probably rabbits."

"Good. Keep breathing. Give me more."

"More insects. In clouds. The stream on the far side of the clearing. You."

"What about me?"

"Your breathing. It's slowed to match mine."

"More."

Fig felt her brow wrinkle. What more was there? She squeezed her knees with her hands.

"You're---" She squeezed harder, pressed in with her fingertips. Beneath the crickets and the wind and the breath, a low humming like the melting caramel of Vaani's voice. "You're humming. Very quietly."

"Good." She could hear Vaani smiling. "Focus on that."

The sound ebbed like a string plucked once.

"It's gone."

"And now?"

The humming resurfaced, louder this time. Fig opened her eyes to see Vaani holding two serrated leaves from the alder, one in each palm.

"I hear it again."

"From where?"

The world dimmed. Fig focused on one leaf, then the other, dark green and alive. They looked identical. Too identical. Even the shadows they cast on Vaani's palm were exactly the same. She leaned forward. She listened.

"The one on the left," she concluded.

"Good," Vaani praised. She closed her left hand and the illusory leaf dissolved in orange haze. She ripped the real one in half, and half again. Its pulp was solid and real in her hands. "You're attuned, alright."

"What exactly does that mean?" Fig rubbed at ears. When her focus broke, her head began to pound.

"Everyone experiences magic differently. I call you 'attuned' because you are capable of sensing it more strongly than others," the witch explained. "That sense might begin to manifest as sound, sight, smell, even something completely foreign. You'll have to learn and practice searching for it, just as you learned and practiced to understand words or speak."

"So I'd never encountered magic before your illusions today?" Fig asked.

"Hardly. More likely you'd never encountered it so concentrated."

Fig pondered that but her head spun.

"May I touch you?" Vaani requested.

Fig nodded. The skin of Vaani's fingers was impossibly soft. She held her hand lightly, as if extending a perch to a bird.

"Focus on my magic again. The humming."

With some effort, Fig found it. Without an active illusion, it was quieter than the insects buzzing in the grass. When she nodded, Vaani lifted Fig's hand and placed her palm against the trunk of the alder. She felt the lines in its bark like scars.

"Think of my magic as the surface of a lake," Vaani instructed. "Dive beneath it."

Fig closed her eyes and cleared her mind of all but the humming. She pushed away the crickets, the wind, the rabbits at the edge of the wood. She moved toward it with resistance as if swimming. She dove. She felt something new beneath her palm before she heard it. A deeper, older vibration. It rumbled like rocks clattering, like the ground parting.

Her brow furrowed. "Is there someone else here?"

"No," Vaani whispered. "What is it?"

It was getting quieter. No, it was moving. It started deep in the dirt and moved up, up, out, spreading thin and faint, ballooning into hundreds of smaller notes.

Fig gasped, "It's the tree, isn't it? The alder."

"Yes." Vaani clapped.

Fig felt a spark of triumph. She sat up straighter. "Does this mean I can do magic?"

"More often than not, the attuned have a capacity for witchcraft."

"What does that mean?"

"Things are changing," Vaani explained, her eyes shining. "Historically, witches were not born. They were made, or summoned, or sculpted, or just appeared. They exploded into existence from moments of beauty, quiet, triumph, carnage. They mightn't be people the way you and I think of people. They were beings created and sustained by magic."

"I've heard stories of witches falling with shooting stars or dripping from stalactites," Fig mused. While her mother did not entertain such follies, the people of town surely did. "Are those true?"

"Many, yes. Though a witch can be known to exaggerate at times," Vaani laughed. "We are dramatic creatures, after all."

"What changed?"

"In part, humanity is advancing into the wilds. Thriving like they couldn't before. Traveling settlements have become villages, villages have become towns, towns, cities."

"There weren't towns before?"

"I'm sure there were," Vaani mused. "Distant, hidden, or too temporary for word of them to spread. I don't need to tell you that the wilds are dangerous. We're in a new and fragile era of communication, of travel. The world is getting smaller."

Fig understood the wilds to be dangerous for others. Her mother came home from her patrols both bloodied and blooded. Whatever creatures of the wood the townspeople feared fell before her blade. Those who strayed where they were not welcome fell just as well. Her mother was as much a danger to nature as the town. Yet her cleansing kept them safe, Fig the safest of all.

"Your turn," Vaani continued. "Fill in some gaps for me."

Fig made an effort to calm her rising nerves. "Where would you like to start?"

"How long have you lived here?"

"Since I was born."

"How?"

"Not part of our deal."

Vaani laughed again. "Fair enough. Tell me about the town."

"It started with just one man. He doesn't leave his house much now. I doubt you saw him this morning. My---" She stopped herself. "I first heard of him when I was young. I almost moved because he arrived. He was the grizzled type, a survivor. Dirty, bearded, scarred. He gave the woods a wide berth except to take wood from the edges. That was acceptable behavior. He prayed often. To what, I don't know. He set up a sturdy shelter, began farming. He lived alone for many years."

The witch hung on her words. "What did he look like? Any particular kind of clothing? Clan markings?"

Fig shrugged. Such things had never seemed important before. "None that I remember. I was a child."

"Understandable," Vaani conceded. Her disappointment was intolerable.

Fig scrambled for more to offer her.

"One winter, a family stumbled in. Two parents and three children, the eldest close to death. They came from the west, had followed the coast. They looked quite different from him. Lighter hair, taller. He took them in. The child died. They stayed."

"Is there anything else you remember about them?"

"They had much less than him. Whatever they were living on, they'd lost it along the way. They wouldn't have lasted much longer."

Vaani's face was still. Fig couldn't tell if this was surprising to her, or if she'd heard many such stories over many such years.

"More people came. At first by accident. Then, over time, on purpose. They sent a few every year back in the direction they'd come from. One in four would return, and return with family, friends, children. They mourn the ones who don't come back. Big long ceremonies. Lots of wasted food. The first man teaches them to farm, to be cautious of everything, to survive. They aren't usually any good at it at first."

"Where do they come from? These late additions?"

"Cities," Fig whispered, superstition creeping across the plains from town. "Some of them travel for moons and moons."

"Is that so?"

Fig couldn't remember the last time she'd talked this much. She'd never told the story of the town before. She couldn't stop. "They've run away. They're shifty the first few weeks, like someone will come after them. No one ever does."

"What are they running from?"

"They're not quick to talk about it, as you know. If you listen at the right corners, they all say they've lost something."

Now Vaani was visibly surprised. "Lost something?"

"They never say what. When they say it, the people who came before just nod and understand. Everyone understands."

"Are they happy?"

It was Fig's turn to be surprised. "I couldn't say. I suppose. They're alive."

"Thank you, Fig," Vaani bowed her head. "You've helped me."

The shock of her final question broke Fig from the stupor she'd felt since they met. The world was again sharp, dangerous. "Why are you here?"

"Not part of the deal."

"Are you going to hurt them?"

"No," Vaani replied immediately, seriously. Fig felt the weight of her earlier promise still in her palm. She believed her.

"Were you born?" Fig asked.

"Excuse me?"

"You said earlier witches were creatures, not people. Like 'you and I.' Were you born?"

"That's a personal question."

Fig said nothing.

Vaani's easy smile returned. The air between them relaxed. "I'll answer because I think it's important to your education. I just don't want you going around asking every witch you meet."

Their meeting had already changed the fundamental texture of Fig's life. She shivered at the thought of meeting another.

"I believe we should start even earlier," Vaani mused. "Allow me to trade you a story for a story. Is that alright?"

Fig nodded and pulled her knees beneath her chin.

"I am what we call an enchantress. Legend says the first enchantress was chiseled from jade." As she spoke, Vaani twisted her hands in a silent rhythm. The summer air coalesced first amber, then orange. "There was, oh, how there was in the oldest of days, a kind miner. This miner and his wife were rich in love only, their mountain home long dry of worth. They lived meagerly and cried into the mountain."

Fig watched in wonder as silhouettes fastened themselves like paper puppets upon the orange air. Man and woman fell to their knees and released fat, shadowy tears.

"Unbeknownst to them, the mountain hid a deep fissure. Their weeping filled the fissure for a hundred days and a hundred nights and hardened into a green stone that grew by layer with each circle of the sun. Finally, on the one hundred and first day, the fissure split." The smoke parted between Vaani's dancing hands. "Inside, a slab of jade. The miner and his wife rejoiced. They took up their tools and struck the gem. What they found," Vaani slowed, "was the most beautiful chiming ever heard, before or after. More beautiful than any bell or bird. A perfect, gorgeous note." The witch removed two green bangles from her wrist and struck them together. Fig gasped alongside the puppet couple at the clear, sweet sound. "As the couple chiseled the jade, they noticed a pattern to its song. They carved at the stone in line with its song as if it were teaching them where to strike."

Vaani began to sing, her voice sweet and wavering over each sound. The shadow couple struck at the stone again and again.

"When the last sliver of jade fell, the jade witch blinked to life. Her form freed by their labor, she embraced them. She had felt their woes trickle beneath the ground, heard their cries and kindnesses. She knew they had soft hearts, that they shared all they could share, that they took only what they were due. She loved them. And from the magic of her love, the mountain filled again with fine stone and precious gems." The three figures danced in spirals through the orange haze. The entire meadow rang with magic.

"For a while, they were rich and happy. Their table was full and the jade witch enjoyed their company. But when word spread over the river of their wealth, people came from across the land, their hearts mired with jealousy. Though the miner and his wife gave from their riches freely, their neighbors wanted more. Endlessly, violently more. They scrambled over the mountain with tools of their own and fought over its riches."

"The jade witch despised destruction. She plucked a strand of her jade hair and strung it from a forked tree branch. When she strummed the strand, every person stilled. They had never heard such a sound. When she opened her mouth to sing, her voice was as melodic as the miner's axe striking jade. The fighting stopped. Each person drawn to the mountain dropped their weapons, enchanted. She sang a song of peace and plenty, of equality and humanity. She sang of her plan to distribute the riches of the mountain evenly, so that every traveler would have their share. That is why you can find gems like these," Vaani gestured at the sparkling jewels in her hair, "throughout the wilds. Legend has it, they were spread across the land by the first of my kind."

Fig resisted the urge to lean closer and touch the gems' polished faces. "What happened to her after that? To the miner and his wife?"

"Who knows? I could come up with any number of things, some true, some not. It's a story, after all." Vaani leaned back against the alder as the haze of her illusions dissipated. "Maybe she went on to found her own city. Or maybe she lived peacefully with the miner and his wife. Or maybe she walked into the ocean until the waves swallowed her whole and sang only for fish."

"Well I don't care for that last one," Fig frowned.

"A witch is beholden to no one. It will aid you to remember that." Vaani gazed up beyond the branches of the alder. "Power makes us different from other people. It makes you feel like you could fit the whole world between your teeth."

Fig stared at her for a few moments in silence.

"So it's true then, that witches run the cities?" she ventured.

"Is that what they say?" Vaani smiled, her veneer of elegance back in place.

"It's what they whisper."

"I can only speak for a few of them. The wilds are vast and voracious. Things are often lost, changed, consumed." She seemed to consider her answer with care. "My kind, enchantresses, are witches drawn to people. Like the jade witch before us, we often seek to live amongst those who need our help. You could say the center of a city is a likely place to find an enchantress, for better or for worse."

Fig scowled, "That doesn't say much of anything."

Vaani laughed her chorus of bells. "Then you're learning about politics this evening as well. Save more questions for tomorrow. That's all for tonight."

Fig traveled home slowly, her footsteps silent in the brush. It was strange to see her home so dark and lifeless in the night. When she curled into bed she dreamed of the jade enchantress and her pale green skin. She was walking on the beach, water caressing her ankles. Fig tried to step towards her but could not move. The enchantress lifted her legs slowly, as if each moment was carved from stone anew. The water was rising. She would disappear soon. Fig called out to her. She turned her head.